AI Promises to Simplify Teachers’ Jobs. It Might Make Them Harder.

Sure, we can offload all our biggest challenges to AI. But what are we telling students about the value of thinking?

The more I learn about AI and writing, the further it falls in my estimation. Forget the education-specific tools, which I’ve found hallucinate just as much as their consumer-oriented counterparts, even the super-powered LLMs have never made my job any easier.

It’s not just that I don’t trust any of the information AI tools spit out (as the recent Google search dustup has proved), it’s more that while they can write faster, they aren’t any better at it than I am. And no matter how much they improve, they’re often considerably worse.

When I wrote headlines, subheads, and social-media copy for Edutopia, it usually took a reasonable amount of time to wordsmith something that was both interesting and aligned with existing conventions. (Keeping in mind Gerunds in headlines were very popular; subheads were punchy and informative). Despite my best efforts at prompt engineering, AI never really grasped things like that. My versions always won the day, even when I would slip in a few AI choices and let the top editors select what would ultimately appear on the site.

As for using it to help rewrite a clunky sentence, sure it often generated a few capable options, but I didn’t get into writing as a career to use technology to avoid the hard parts of writing. (Except perhaps when whiling away the days on YouTube).

It’s not much of a take to say that writing well is difficult. So is thinking critically. But, crucially, both endeavors help me better understand topics when I have to explain them for others. In other words, doing things on my own is the helpful part. So what are these tools doing in education beyond the marketing claims of “saving time” and “personalizing learning,” and what do we stand to lose?

A lot, it turns out.

Over the past two years, a glut of human-written words have been published on subjects such as these, and what AI might mean for the future of the teaching profession. Tools like ChatGPT are only getting cheaper and more powerful, upending our current system of assignments and grading. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but it is a seismic shift, and it’s happening quickly.

AI tools are frequently marketed to teachers as time savers, even while students are told to use them ethically and responsibly with too few red flags being raised. It’s not going over well, and it gets even worse when you consider that all this just showed up one day, virtually out of the blue.

“The maddening thing about all of this is that these tools are being deployed publicly in a grand experiment nobody asked for,” Marc Watkins, an academic and AI literacy expert, said recently.

Watkins is one of the leading critics on AI tools being adopted, well, uncritically in education. Though these days, he’s got plenty of company.

Below are some of the best arguments I’ve seen against using AI in the classroom, but also for teaching students to think for themselves.

First up is high school teacher Liz Schulman who explains in the Boston Globe just what we’re losing in the age of unrestricted ChatGPT — namely, the very capacity for original thought.

ChatGPT eliminates the symbiotic relationship between thinking and writing and takes away the developmental stage when students learn to be that most coveted of qualities: original.

Isn’t originality the key to innovation, and isn’t innovation the engine for the 21st century economy, the world our students are preparing to enter?

You can sense the aliveness in the classroom when students use their imagination and generate their own ideas. Their eyes become warm. They’re not afraid to make mistakes, to shape and reshape their ideas. The energy shifts. I’ve seen it happen in their discussions and with stages of the writing process, from brainstorming to drafts to silly stories to final essays. They’re more invested in arguing their points because they’ve thought of them themselves.

Next, let’s check-in with Watkins over at Rhetorica, in a piece on subtly replacing teachers, on why AI is a credible threat to education—and why education is, of course, more than a means-to-an-end.

Yes, every teacher knows the learning is the most valuable part, not the letter grade or the degree. But does every standardized test maker know that? What about students or parents or school board members or edtech companies? (Or Sam Altman?)

A sizable number of people view education as an entirely transactional relationship—learning as a means to an end. For this crowd, using AI to replace traditional teaching or augment it is perfectly acceptable, even warranted. They don’t see learning as intrinsically valuable or think about the human relationships at the heart of teaching. Critical thinking, ethical decision-making, and contending with views different than your own aren’t on the agenda of a transactionalist view of education. Removing any barrier to getting a degree matters most to these folks, so too, does ensuring a student consumer likes the content they’re provided. And that is a much deeper problem.

…

When you reduce education to a transactional relationship and start treating learning as a commodity, you risk turning education into a customer-service problem for AI to solve instead of a public good for society. Making my education my way might remove certain friction for some students to achieve academic success but at an immense cost. We’re already siloed by algorithms in social media, do we really want to create silos in education, too?

That reminded me of something writing instruction expert John Warner wrote more than a year ago in his classic essay, ChatGPT Can't Kill Anything Worth Preserving, on why writing instruction is vulnerable to AI, but good writing instruction is not. Truly, teachers have their work cut out for them when it comes to working with students and helping them see the inherent value in learning how to write and think over shortcuts like using an algorithm.

Teaching in the age of AI might get even harder, and not the kind of hard that can easily be solved by prompting an LLM.

But the reason why I’m confident my pedagogy is not vulnerable to ChatGPT is because I do not only grade the end product, but instead, value the process it takes to get there. I ask students to describe how and why they did certain things. I collect the work product that precedes the final document.

I talk to the students, one-on-one about themselves, about their work.

If we assume students want to learn - and I do - we should show our interest in their learning, rather than their performance.

Unfortunately, for the vast majority of my career, I did not have the time or resources necessary to fulfill the highest aims of my own pedagogy. The National Council for Teachers of English (NCTE) recommends each instructor teach three sections of a maximum of fifteen students each, for a total of 45 students. I never had fewer than 65 students in a semester, and some semesters had in excess of 150.

High school teachers are working under even greater burdens, and in more challenging circumstances. If the system will not support the teachers who must do the work, we may as well let ourselves be overwhelmed by the algorithm.

Elsewhere, in another piece, Marc Watkins argues against the prevailing narrative that AI tools might be the ultimate time saver for teachers—the new silver bullet that will save them hours by streamlining everything. Because AI doesn’t think, it pattern matches. It can only “cobble together information from its training data into a competent output.” It doesn’t understand anything about pedagogy, students, or ethical decision making. So what exactly is being gained by offloading tasks to it?

Effective teaching requires intention—aligning objectives, assessments, and activities in a cohesive plan. AI struggles with this and requires a user to align these areas using their own judgment. This takes a great deal of time and human skill. Generative tools can create activities, but AI cannot grasp the pedagogical foundations to purposefully scaffold learning toward defined goals. That’s a teacher’s job. The risk of using these tools uncritically as time savers is students end up with a disjointed collection of tasks rather than a structured experience.

No AI tool truly can account for who your students are. Only skilled teachers can design lessons centered on their specific students' backgrounds, prior knowledge, motivations, etc. Used intentionally in this way, AI can certainly help augment a teacher, but again, that takes time and friction. AI alone can't analyze and adapt to a classroom's dynamics like a human being can. If we use AI like this, we'd be stuck with one-size-fits-all instruction disconnected from those human realities.

In other words, it can’t teach.

Edtech professor Evi Wusk also resists the idea that it’s simplifying our lives for the better in an essay for EdSurge. A common theme running through these types of articles is that an LLM can’t think, and thus can’t do our thinking for us. We all know that modern teaching is too time consuming and demanding. But there’s real value in not saving time using AI in the same way that there’s value in solving a tough Wordle versus looking up the answer online.

As AI becomes more mainstream, it leads me to philosophical questions, but on a practical level, I find it interesting that so many of the things I’ve learned that matter to me the most were hard. They took effort. They took time. Learning them was rewarding.

I don’t want to forget how satisfying it feels to clear off a garden, to grow stronger at something through extended practice or to create something from scratch. I don’t want our schools to forget either. As Tom Hanks says in, “A League of Their Own,” “It’s supposed to be hard. If it wasn’t hard, everyone would do it. The hard… is what makes it great.”

Reading through these pieces helped me gain a better understanding of what’s at stake. Writing this post helped even more, especially to organize a lot of thoughts I hadn’t really articulated to myself and to make connections between a bunch of different pieces I’ve hastily read and bookmarked over the past month or two.

And sure, I could have probably asked AI to do a lot of this pattern matching for me, and I might have even saved myself an hour or two.

But what would I have learned from that?

👁 👄 👁 Show & Tell

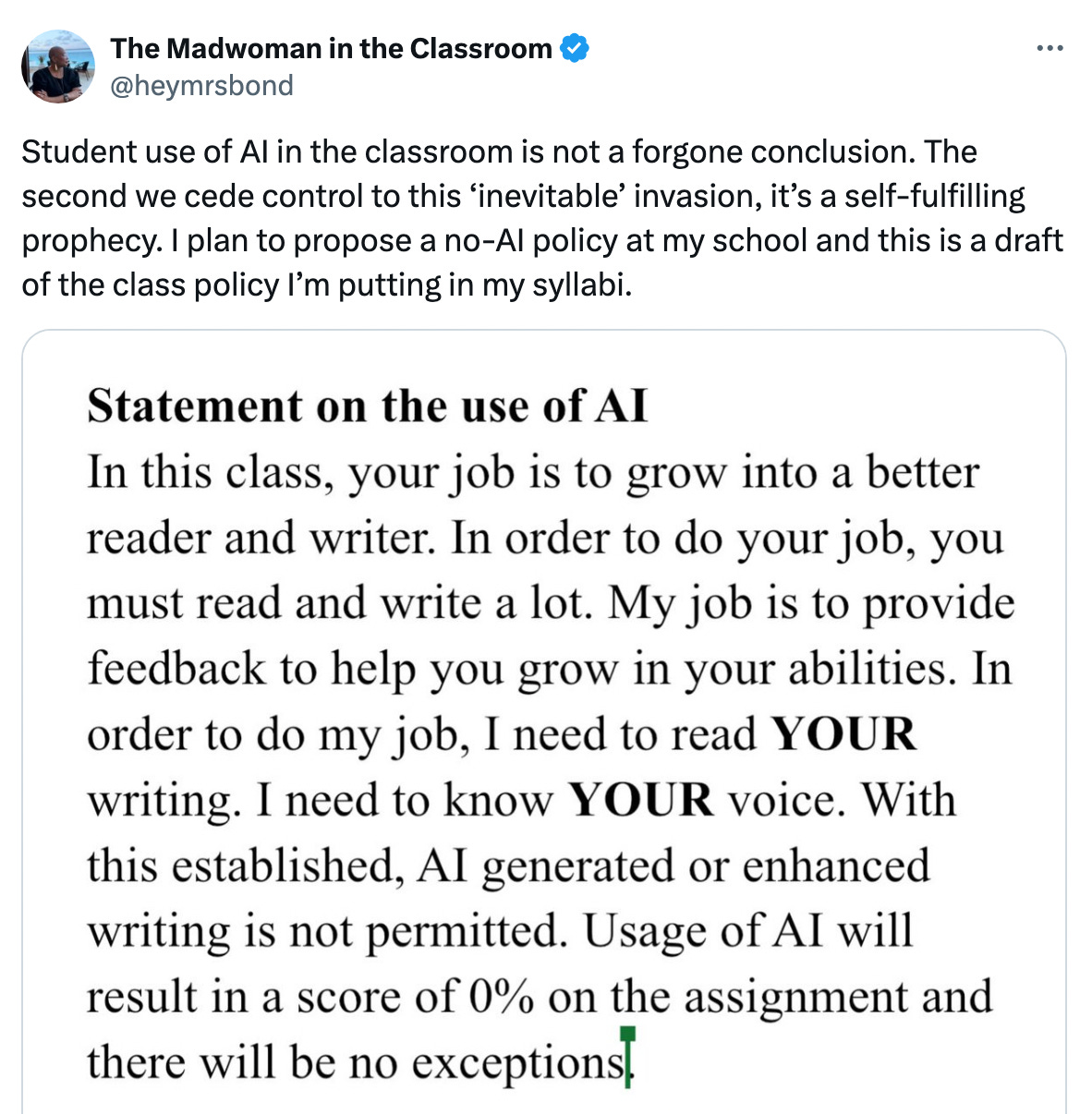

Another great quote, which could have fit in above, about the “inevitability” of AI, i.e., that it’s only as inevitable as we make it (via @heymrsbond on X/Twitter).

📚 Independent Reading

Wall Street Journal (free link): It’s a themed issue around here this week apparently. Next up: Is AI any good at grading papers? Sometimes, maybe. But then again, “It should not be used for grading,” said Alex Kotran, co-founder of the AI Education Project, which teaches AI literacy. “It’s going to undermine trust in the education system.” This article then spends another thousand words detailing exactly how AI is currently doing just that, including tales of students asking teachers for higher grades based on the higher marks AI gave their work. Of course, AI grading, in the WSJ’s own estimation, is often all over the place. One paper run through different tools scored anywhere from a 62 to a perfect 100.

Hechinger Report: Emerging research shows humans are a bit better at grading than AI, but scores are close. Humans are better at giving useful feedback for improvement, though. “It was better than I thought it was going to be because I didn’t have a lot of hope that it was going to be that good,” said Steve Graham, a well-regarded expert on writing instruction at Arizona State University, and a member of the study’s research team. (Of course if students know it can provide great feedback, they surely know it can write a good paper too, he adds). At the end, writer Jill Barshay asks ChatGPT to grade her own first draft, and found the generated feedback either superficial or irrelevant—something I’ve noticed when asking it to judge my own writing. (AI did, however, provide a handy list of other writers with a style and tone somewhat similar to my own, which I greatly enjoyed.)

New York Times: I think we’ve all earned a bit of a reprieve from thinking about AI. How about the joys and challenges of being a male kindergarten teacher? Only 3 percent of the kindergarten teaching profession is male, but they can impact kids in ways big and small. Some great photos here too.